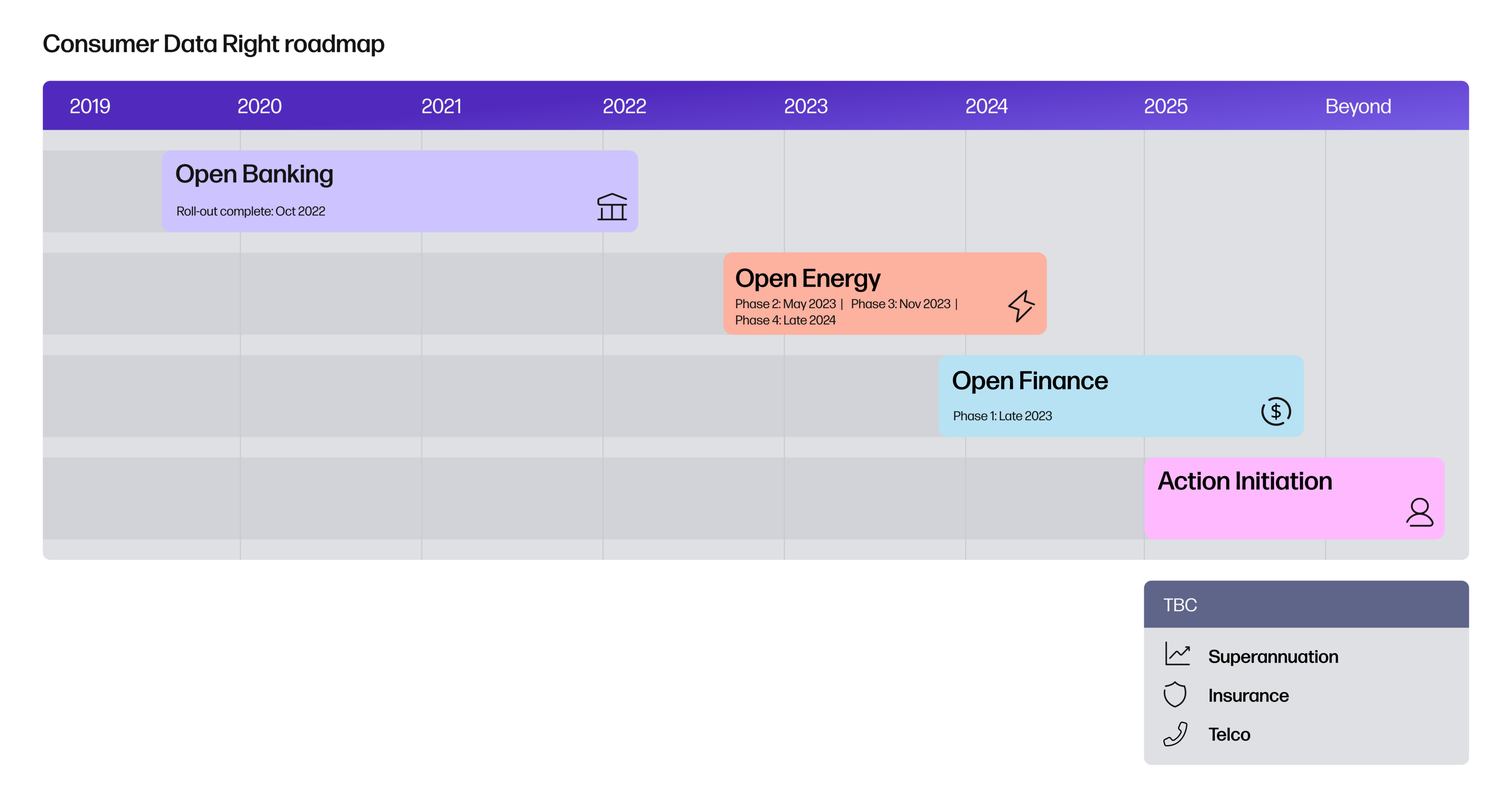

It’s been over 3 years since Australia’s Consumer Data Right (CDR) launched – an economy-wide initiative developed to give consumers control over their own data, increase competition and innovation, and deliver better consumer outcomes. It was always a big (but achievable) goal, needing a strong regulatory framework and sophisticated systems and processes to make the right data reliably available in a way that’s easy to use for consumers and businesses.

The banking sector was the first data-sharing cab off the rank, following in the footsteps of Open Banking systems already in operation in Europe and the UK. The CDR roll-out in the banking sector required over 100 Australian banks to make it possible for customers to share their data with accredited third parties.

Open Banking is now an established part of the Australian banking system – and it’s still evolving as business use cases are tested and its potential is realised. This isn’t expected to change anytime soon, as its evolution is part of it growing and delivering the right outcomes for consumers and businesses. But change isn’t anything new in business, and we’re seeing businesses and Data Holders adapting to a regulatory framework that is continually evolving. People and processes inside these businesses are now used to working with an ever-changing regulatory regime.

However, like any regime the size and scale of Open Banking, such as NBN or mobile number portability, demonstrated results take time. And the roll-out hasn’t been without its speedbumps, as businesses invest in technology and adapt their systems and processes to meet regulatory needs and participate in the regime. But the regulations themselves have also been refined to improve the system and make participation easier.

While more businesses are actively using Open Banking data, many are still taking a more reserved approach, waiting for evidence of how it can benefit their business and exploring identified use cases relevant to their operations. In this next phase of Open Banking, and as the CDR extends beyond the banking sector, the regime will be driven by early adopters prepared to challenge and test the regulatory framework in order to deliver value to consumers.

Reflecting this, the Australian Government announced in the 2024 budget a pause on the roll-out of CDR into additional sectors like superannuation, insurance and telco. Instead, the government committed to a focus on improvements in existing sectors, additional financial datasets in non-bank lending and building the framework for Action Initiation.

The roll-out

Done but not dusted

As we move on from the phased roll-out of the CDR in the banking sector, we can take stock of the implementation of Open Banking in Australia. As you would expect at the completion of a roll-out, the numbers are strong.

According to the Treasury, 99.74% of household deposits are currently covered by CDR data-sharing – near total coverage.

On the business end, as of 18 August 2023, 76 Data Holders were active in banking, with a combined total of 115 brands. Six brands are not active yet.

And with the roll-out of datasets that were initially in scope complete, 31 different types of financial products are available for data sharing, including transaction accounts, savings accounts, home loans, mortgage offset accounts and personal loans.

However, there is still more to come, with the CDR set to expand into the non-bank lending sector. As part of this, Buy Now Pay Later products will be covered under the CDR. Banks must also share data for these products if they offer them.

Ongoing improvements

Despite the initial roll-out of the CDR to the banking sector being complete, updates are still regularly being made to the standards and guidelines. These include, for example, updates to fix issues with data quality and consents.

In July 2023, Treasury announced updated rules to make it easier for business customers to share their data with unaccredited technology providers.

The Data Standards Board also published a design paper about consents in August 2023. It proposes improvements to streamline the consent process to support a better consumer experience while maintaining key consumer protections.

Performance

Fast but loose

With the Open Banking regime now firmly in place, the focus turns to analysing performance measures to truly assess the success of the roll-out.

Speed and reliability

On the surface, the numbers once again look good. Open Banking APIs have generally been fast and reliable for a few years now. Currently, the average Data Holder provides transaction data in 1.06 seconds with 99% reliability. But speed and reliability, while important, are just the beginning.

Consent attempts

A more useful performance metric is the conversion rate – the percentage of successful attempts to complete the consent process. After all, ultimate speed and reliability depend on consent, as that’s the ticket that opens the door for data sharing. And when it comes to consent success, there’s room for improvement.

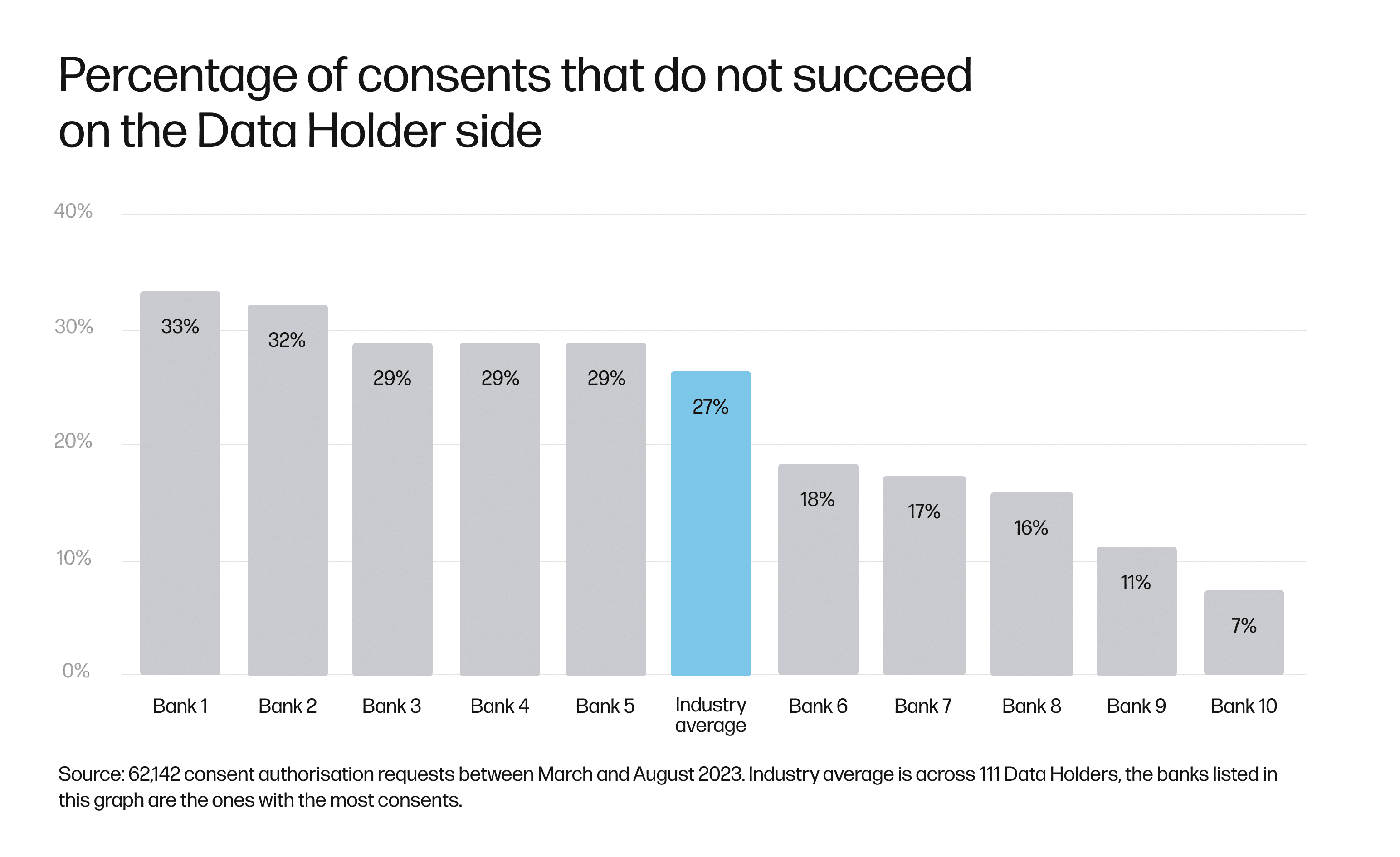

An analysis of consent conversion collected in the Frollo consumer app between January and August 2023 found that 27% of consent attempts fail on the Data Holder side, after the consent has been collected by the Data Recipient. Out of the Big Four banks, only one performed significantly better, with a failure rate of 18%. Out of the top 10 most popular Data Holders, Up performed best, with only 7% of consents failing.

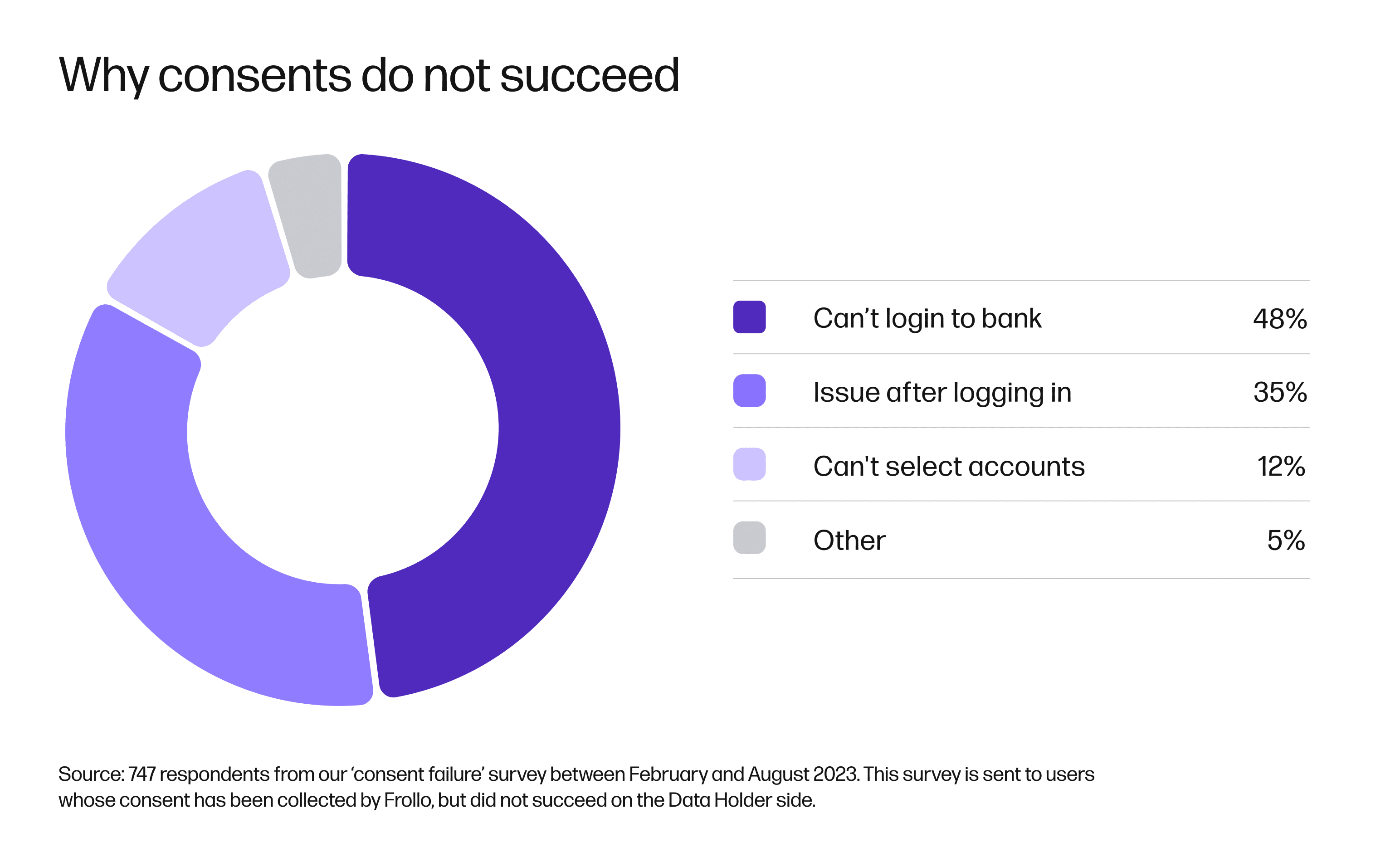

Understanding why so many attempts fail requires diving a little deeper. So, we surveyed 747 people who didn’t successfully link their accounts to help establish where the problem lies. We found:

- For almost half of the users who didn’t successfully link their account, it was because they couldn’t log in to their bank. The majority of these users had issues with their bank-issued One Time Password (OTP)

- Just over a third had issues after logging into their bank, including error messages and not being sent back to the Frollo app to complete the account linking

- 12% weren’t able to select the account to which they wanted to link. In most cases, the bank indicated these accounts weren’t eligible for data sharing. Most of these accounts were joint or business accounts.

These results suggest that the failures, while frustrating for users, are a fixable problem if Data Holders address issues in their systems.

Quality of data

Another important measure of performance is the quality of data delivered through the Consumer Data Right. For Open Banking to deliver value, it’s critical that shared data is reliable and usable.

It’s a little trickier to measure, however the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) completed a stakeholder consultation about data quality in April 2023, which provides some key insights. These include:

- The quality of consumer data is generally sufficient to support the delivery of CDR products and services, although improvements are required.

- There are significant shortcomings in the quality of Product Reference Data.

- Data recipients and users of Product Reference Data have raised concerns over the responsiveness of data holders when data quality issues have been raised with them.

- There is scope to clarify the nature of data quality obligations to ensure a better understanding of expectations around appropriate data quality.

- Regulators should be prepared to take a stronger regulatory approach to improve data quality.

Our own analysis published as part of the State of Open Banking 2023 also echoes the finding that data quality was generally sufficient.

The big one to note is the quality of Product Reference Data (PRD). As the name suggests, PRD is data about products, not people – information like product names, descriptions, rates and fees. Shortcomings in this data hinder the effective use of comparison services.

The irony here is PRD is available via publicly accessible APIs with no consumer consent required. So, it’s the low-risk, publicly available data that’s falling short. Meanwhile, personal consumer data available via CDR, including things like transaction data and customer information, does require consent and is being shared adequately to support CDR services that provide value to consumers.

That’s not to say consumer data isn’t without its issues, and resolving these issues isn’t an overnight fix, given the complexity in data holder systems. It’s also not always a priority for some data holders still dealing with the challenges of implementing their CDR obligations.

However, CDR participants must comply with their obligations and data holders are expected by the ACCC to maintain quality CDR solutions. Not surprisingly, data quality is a priority area for the ACCC and the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), with compliance and enforcement efforts to be focussed on regulatory action for data quality issues involving:

- the provision of incorrect interest rates

- missing data

- the use of free text fields where a relevant structured field exists

- data that is not commensurate with what a consumer can otherwise see in their online or mobile banking channels.

Screen scraping

Security in the spotlight

Now that the initial Open Banking roll-out is complete, the government has announced a consultation on screen scraping. It’s come into the spotlight as Open Banking offers a viable (and more secure) alternative to a potentially risky practice. For years, banks have warned their customers that they shouldn’t share their online banking credentials with screen scraping providers because of the security and privacy risks. Yet, many lenders, investment apps and budgeting tools were built – and became popular – using screen scraping.

On the flip side, the independent 2022 Statutory Review of the Consumer Data Right actually recommended banning screen scraping where the CDR is a viable alternative – which the government is considering for banking accounts. A stakeholder consultation launched at the end of 2023, closing on 25 October. The consultation is welcome, as consumers shouldn’t have to share their online banking credentials to get a loan. But in the meantime, it leaves the market in limbo. A clear signal from the government on when and how the implementation of the ban would take effect would provide certainty and adequate time for businesses to transition, along with stronger incentives to invest in moving to the CDR.

This article is part of the State of Open Banking 2024, an industry report by Open Banking provider Frollo, providing a pulse check of the Consumer Data Right, its participants and consumer uptake.